Mqm new organisation registration#

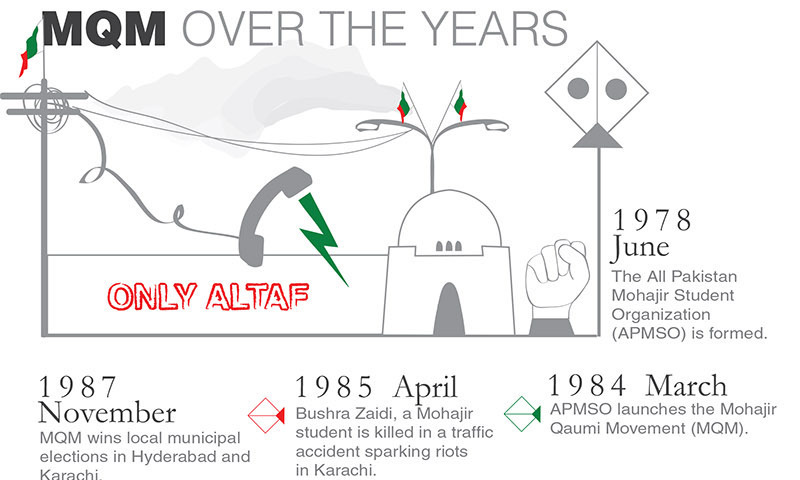

The act was followed by the arrests of party officials, and registration of cases against them. In a fiery speech to party workers in the hunger strike camp outside Karachi Press Club, he raised anti-Pakistan slogans and incited an attack on the ARY News office. He touched a new low on August 22 last year. The Lahore High Court banned his live broadcasts when he criticised and threatened security institutions in his speeches. MQM supremo Hussain’s telephonic addresses, during all those years, resulted in adding to the woes of the party. Kamal laments that Hussain has turned party workers into hardened criminals. Kamal derides him and his politics, holding him responsible for ravaging the Urdu-speaking community, resorting to violence and killing party supporters and opponents alike in the last three decades. His narrative centres around the persona of Altaf Hussain. He has opened offices in almost all MQM strongholds. Slowly but surely, Kamal is expanding his sphere of influence. Instead, he came with a party name derived from the national anthem. But unlike the two, Kamal neither rode an army jeep to capture MQM territories by force, nor did he confine himself to the politics of the Mohajirs. They returned in the aftermath of the military action against the MQM in the early nineties. Kamal’s return to Karachi resembled the return of Aamir Khan and Afaq Ahmed of the MQM-Haqiqi, who had been expelled from the party and chose to live abroad. The party, which was notorious for resorting to violence and agitational politics against the government, and for manipulating elections through its highly organised network across the city, faced a major blow last year when some of its former members joined hands to form the Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP), headed by Karachi’s former mayor, Mustafa Kamal. The MQM-P has been going through a rough phase since 2013, when operations by law enforcement agencies crippled its powers, and decimated its organisational structure. The figures, which run in stark contrast to the estimates of experts on Karachi and urbanisation, are a blessing in disguise for a party whose leadership had started questioning the veracity of the numbers in their initial responses. As cultural critic, Ahmer Naqvi, describes it in one of his writings, “The word ziyaadti - injustice - came up, unprompted, in just about every interview, and it reflects the view that those based in Karachi are outside the system - a system that will always seek to attack and marginalise them.” The estimated population of Karachi, according to the provisional census figures, has sparked a debate, fuelling the decades-old narrative in the city of discrimination and injustice.

In return, it was expecting to be given some political space and be allowed to open those offices in Karachi that were closed after Altaf Hussain’s seditious speech last year.* Additionally, a Rs 25 billion package for Karachi was announced by the federal government - a move that will help the MQM-P in improving the performance of its elected members in local government bodies. The party, known for its political manoeuvering, voted for Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) prime ministerial candidate. Muttahida Qaumi Movement Pakistan (MQM-P), the fourth largest political force in the country and the second largest in Sindh - in terms of its parliamentary representation - has got a new lifeline.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)